An urgent need to increase focus on natural flood management was at the top of the agenda of a roundtable meeting between Environment Minister Rebecca Pow, MPs and local authorities held in Hebden Bridge yesterday.

It comes as northern England’s Pennine communities prepare to spend yet another winter on flood alert, ready for the prospect of rivers once again bursting their banks and intruding into homes and businesses, and costing the economy millions of pounds in disruption and damages.

In recent years, Defra has rightly come to recognise that investing in habitat restoration projects to hold floodwater back upstream is often more cost effective than building flood barriers downstream which can sometimes serve only to shift the problem elsewhere. Indeed, restoring moorlands to their natural, waterlogged state has been shown to slow the flow of run-off water from upland peat by up to 75% to help prevent flooding the valleys below.

But Defra has a challenge on its hands. Many of the Pennine communities impacted by floods sit in the shadow of vast grouse shooting moors where peatland has been degraded by a decades long programme of intensive management. With one hand some of these grouse moors are promising to rewet and restore peatland and with the other they continue to burn on it in an annual ceremony performed to provide younger, more nutritious heather shoots for game birds to eat.

Like many others, Wild Moors welcomed the news in May that Defra had introduced new rules to stop grouse moors setting fire to some of England’s most sensitive peatland sites. But while we applaud much of the work that Defra has done to elevate environmental standards, we are concerned that the regulations on burning still fall short. It is clear that by only introducing a partial ban on burning Defra’s new legislation will leave many areas of degraded shallow peatland behind, despite it needing to be restored to its healthier, deeper state.

In less than a month grouse moors will mark the opening of the burning season, on 1 October, by torching those of England’s carbon-rich peatlands not captured by the new rules. As Defra has acknowledged, “burning is damaging to peatland formation” and “makes it difficult or impossible to restore these habitats to their natural state”. This is particularly pertinent to communities in Yorkshire, Lancashire and the North East impacted by the flooding of rivers with their headwaters situated in Pennine peatland. These communities have a clear stake in the state of the upland peat around the headwaters of local rivers, the health of which has a direct impact on the wellbeing of citizens.

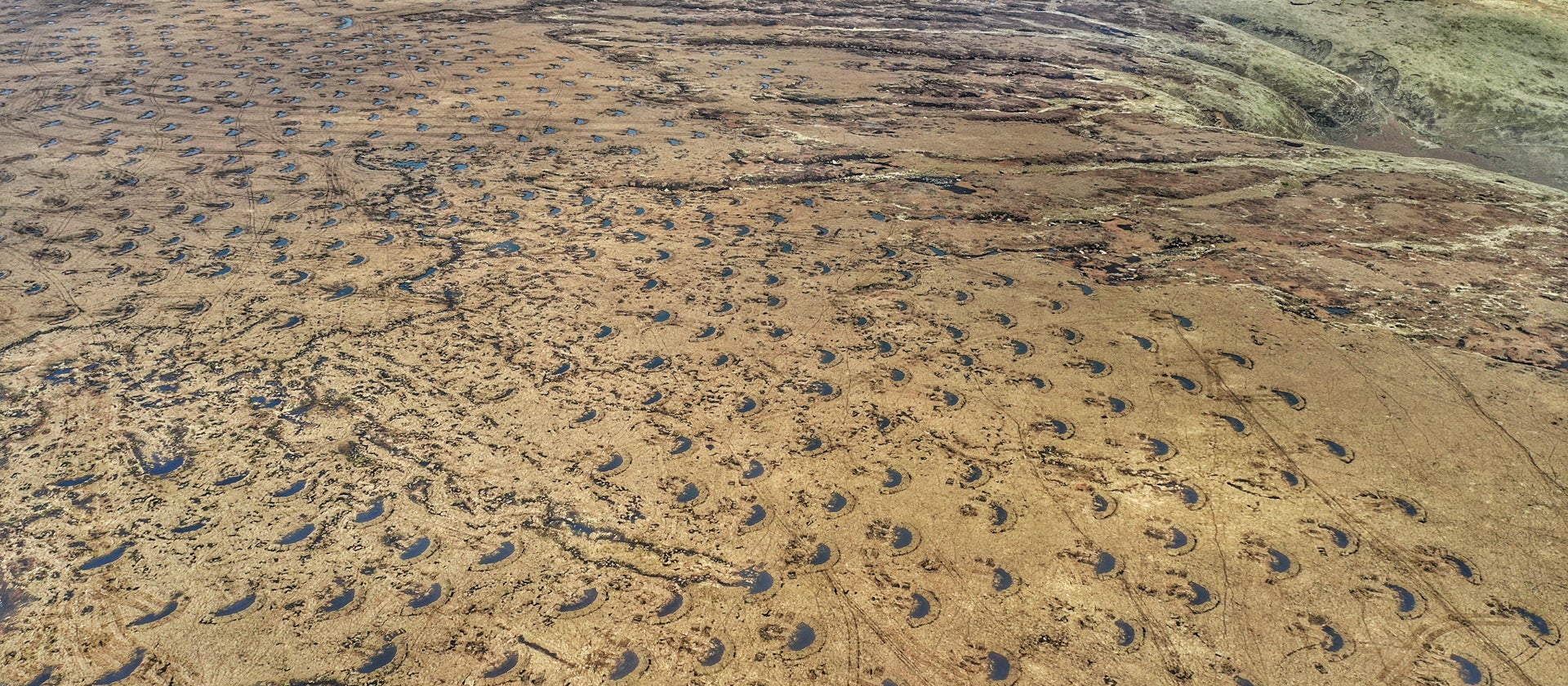

The good news is that a landscape-scale peatland restoration project has commenced on a former grouse moor above Bury, transforming a vast area of degraded moorland into a ‘giant sponge’ to tackle the effects of climate change and flooding. Conservationists have constructed almost 3,500 peat ‘bunds’, scallop-shaped banks which hold water behind them. The National Trust, which is helping to run the regeneration project, recently said it believes the interventions may already have had an effect, as flood-prone communities at the bottom of the moor avoided damage during Storm Christoph earlier this year.

With the UN Climate Change Conference fast approaching, Britain has a prime opportunity to be a trailblazer in nature-friendly land management such as that being carried out on the moors above Bury. As COP26 President Alok Sharma MP says “The world is dangerously close to running out of time to stop a climate change catastrophe. We can’t afford to wait two years, five years, 10 years – this is the moment. This year, this has to change. We need real action right here right now.”